heart open as the sky

Why do people care about "showing up?"

I’ve been feeling a lack of romance in my life lately—a good friend and I had a long conversation about how isolating heartbreak can be, hers romantic, mine platonic. Over dirty martinis and an incredible red pesto pasta, we discussed how we were both handling rejection and the creative waves of energy that flow throughout during a time of heightened emotional anguish. We agreed that the typical stages of grief (denial, anger, so on so forth) don’t seem to capture the wild and feral girl journaling or surges of creativity that precede a full physical and mental crash-out. The burnout comes quick, exactly when you might think you’ve figured it out, cracked the code, and are ready to move on, perhaps even saying aloud to yourself, I’m ready to move on. That’s precisely when the depression hits.

Summer of 2025 was never going to be perfect, I knew that. I knew that July held a major surgery with a long recovery time, and that we were moving to a city two hours away from most of our friends. At that point, I was deeply unprepared to be unceremoniously dumped. It was less of bringing a knife to a gun fight as it was, say, bringing a talking stick to death row.

But in the midst of all of this, I kept coming back to the idea of self-imposed isolation. Since the last time that I dealt with something like this, I spent three years seeing a Buddhist therapist, her Jewish heritage also informed her school of thought. I started reading the Tao Te Ching during those years, and have been rereading it recently. It’s pretty unflinchingly clear: caring about other’s approval makes you their prisoner.

To be clear, not caring what others think is not solipsistic or prideful, because it does not absolve you from living in truth. You don’t get to not care what others think, and also live in your own delusions. The assumption here is that if you are living a truly authentic life, then it is not hard to let things go, you can trust in your self-knowledge, and trust your natural responses (23) without intensive overthinking or second-guessing. (And if you can’t trust your natural responses, perhaps that should also be a sign not to trust the overthinking bit; “Not knowing is true knowledge… First realize that you are sick, then you can move towards health.” 71) What you think that others think about you is not relevant (or even true, since, as a reminder, you don’t know what another person thinks about you), so it becomes easy to not let it affect how you act. A better way of putting it, as this brilliant article did, is that those truly confident in themselves demand nothing of you.

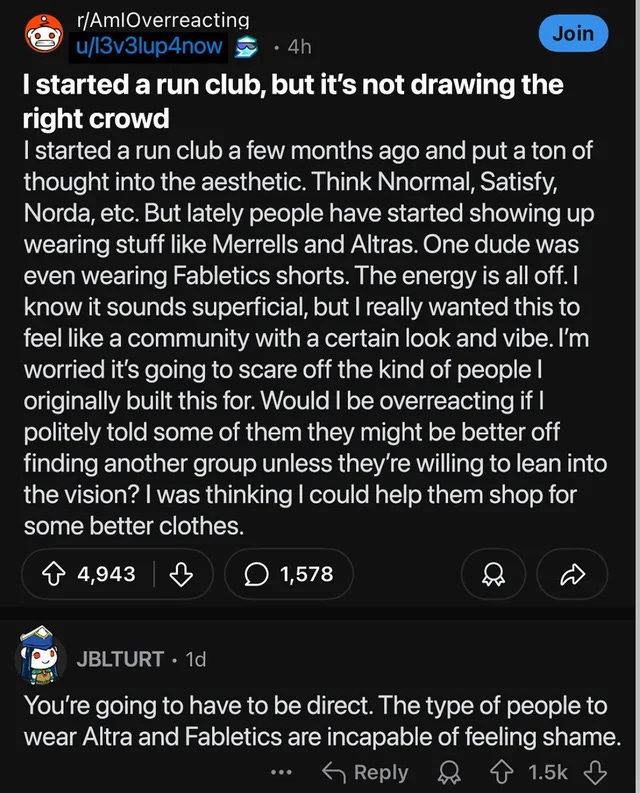

Do we live in a “showing up” culture? In which our engagement with our communities is highly conditional, and dependent on how others meet our highly specific demands? A sort of tit-for-tat way of looking at the world in which, as soon as someone falls short of your vision for [insert: love, siblinghood, friendship, or, see below, run club] they are not only wrong, but somehow have earned rejection? Living this way offers the illusion that you will never be hurt, because you never give until you have received. Additionally, this sounds exhausting.

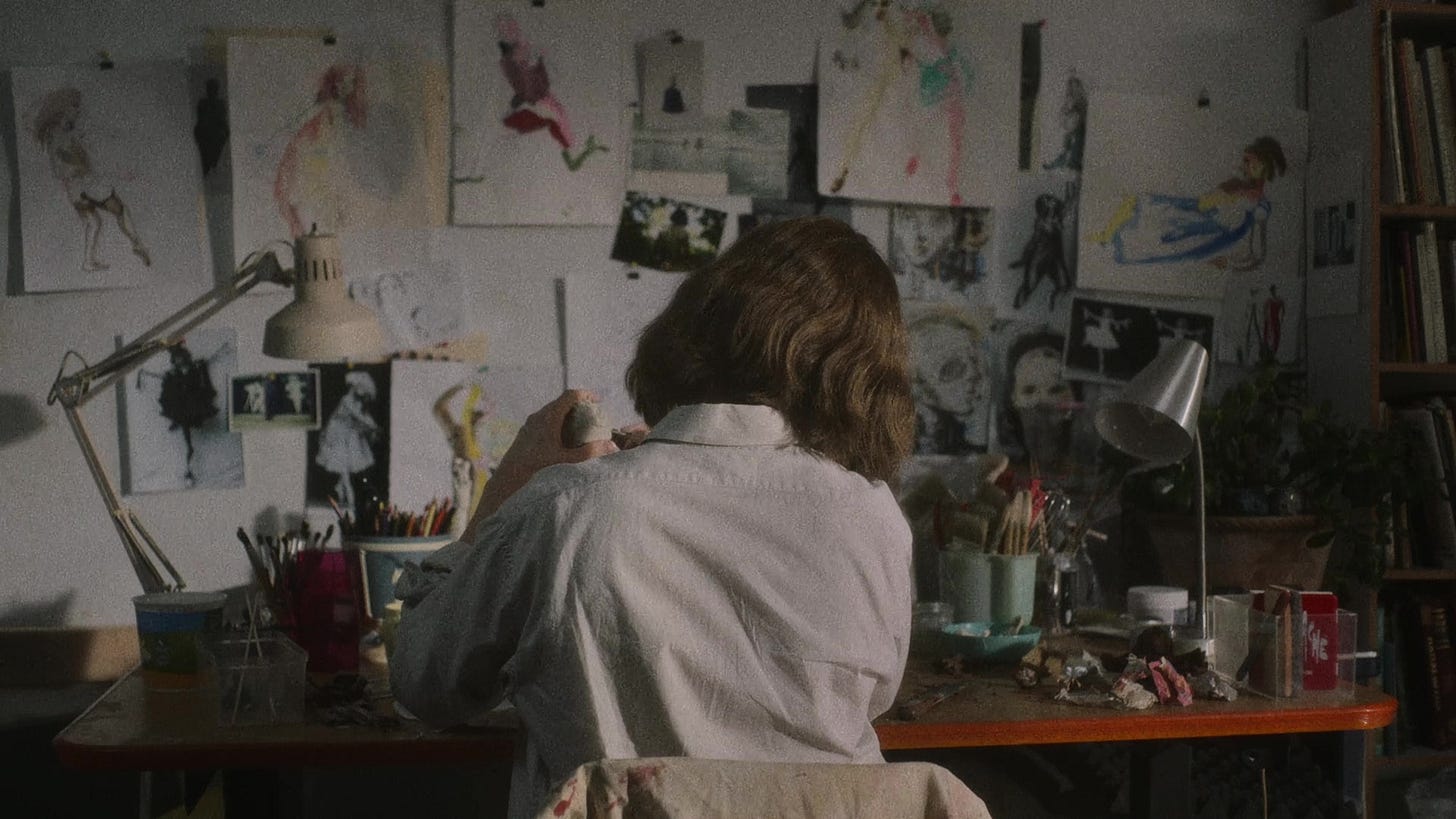

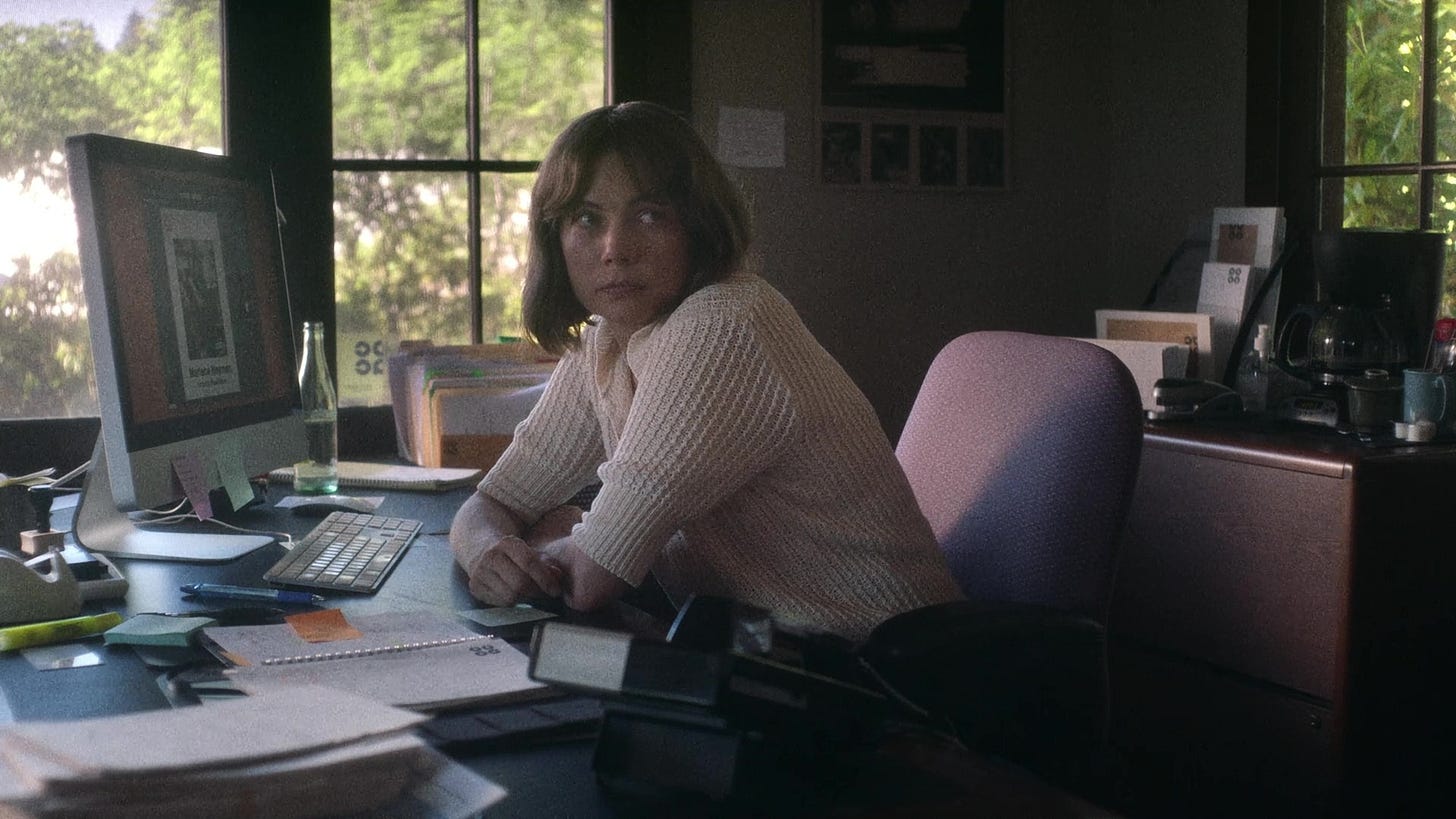

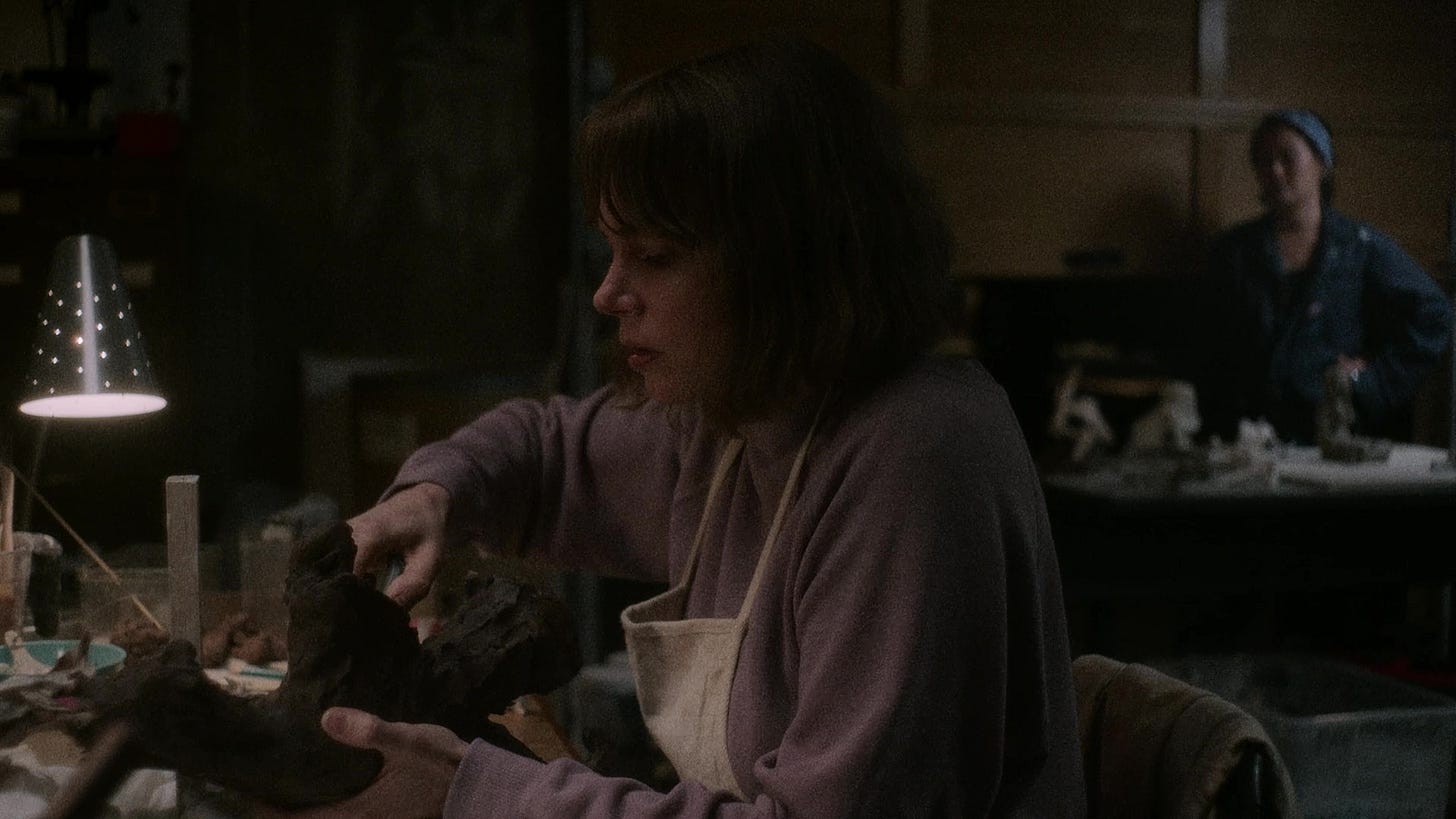

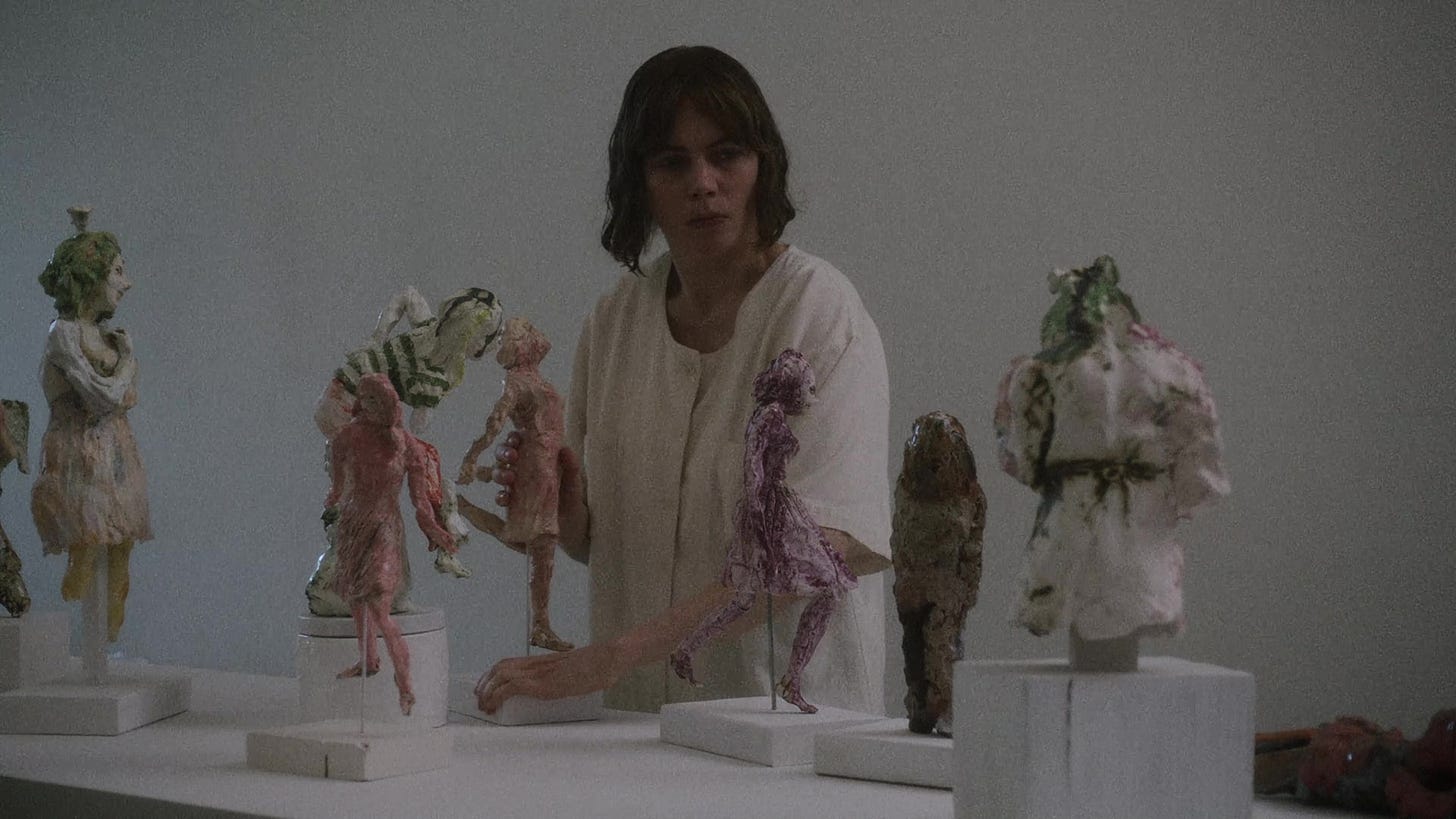

The idea of showing up was well explored in the Kelly Reichardt film of the same name. Sculptor Lizzy (Michelle Williams) is surrounded by others, but lives and works in relative solitude. She seems, nonetheless, to be completely creatively and emotionally fulfilled. Her conflict is in perceiving that others have reached that same level of happiness and fulfillment without making the sacrifices she has to live an “artist’s life.” Those who engage in community differently than she does is insulting and inauthentic to her. AKA, she is the perfect martyr archetype. She believes that they way she interacts with her work is the true way, and witnessing others own ways becomes somewhere between a minor inconvenience (she truly does enjoy her solitude) and a personal affront. She categorizes the peculiarities of how they “show up” (for each other, for her) as an act of violence towards her.

She feels a disappointment in her community and also a disappointment in the facts that she feels disappointment that reveals her immaturity. Her disappointment is not quite jealousy, but looks a whole lot like it. She is incapable of putting herself into situations that make her feel uncomfortable, but simultaneously, has created a life for herself where she is genuinely mostly happy without doing so. The crux of the film comes when people “show up” for her gallery opening in a very supportive, but ultimately “wrong” way. Whatever is wrong about it is only clear to Lizzy, and without being prescriptive, Reichardt hints at the question, are we all way too fucking self-absorbed? Or perhaps more sympathetically, is it okay to forgo deep personal connection to be happily self-absorbed? There is no answer, but continued day to day life and Lizzy’s satisfaction having a shallow, but mostly peaceful connection to her community.

The question I’m left with in this film is does Lizzy truly demand nothing of her community? Or is it her prideful indifference to her community that reveals exactly how much she cares?

I have wondered a lot about this concept of showing up. Is it wrong for people to have different ways of showing up? I have a friend who is relentlessly considerate: she made a care package for me when I went into surgery, she sends thank-you cards and hosts huge parties and is generous with her money and time. Is she more or less winning at “showing up” than another friend, who texted “Omg, did you have surgery?” four weeks after I told her I was having surgery, and then we ate croissants and I told her about how mind-bogglingly painful was the experience that she was utterly absent for. Are you keeping score in friendships? I can say that I honestly haven’t, though the temptation to has been curiously higher in this dark season.

Let me rephrase, the temptation to police my friends’ behavior has curiously correlated with pain. And the inevitable irony is that policing my friends behavior perpetuates a further cycle of pain and lashing out.

Here’s my own hard truth: my isolation has been self-imposed. I have let one person’s actions speak for the many because the animal of rejection is a hungry beast, and there is no amount of feeding it that will satiate it. The harder thing is to acknowledge the rejection, treat feelings as flags rippling in the changing winds, and instead, trust in your strength and move on.

If you accept the world [as it is], the Tao will be luminous inside of you, and you will return to your primal self.

When moving on leaves you feeling empty, and depression takes hold, that’s a sign that you have been emptying yourself out to make space for insecurity, anger and resentment. Have you ever stopped feeling angry, then just simply felt nothing at all? What has to follow is a conscious effort to reconnect with goodness, to approach your friends and community with open hands, and let that darkness be filled up with the generosity of others. There is no clawing your way back to peace, there is no revenge, you have to kill the cop in your head.

You too, are most likely the only person at fault for your own feelings of isolation, and if you don’t think that’s true, reconsider. The truth of that should be a massive relief. As the self-absorbed response is, people aren’t considering me, the enlightened response is, if I look to others for fulfillment, I will never be truly fulfilled. Is your purpose to be fulfilled? Or is it to be right?

The master observes the world, but trusts her inner vision. She allows things to come and go, her heart is open as the sky.

Thanks for this essay - I’ll be seeking the film out 🤍🐱